Magical theory

Why insist, against all hope, on the communist idea? Is such insistence not an exemplary case of the narcissism of the lost cause? And does such narcissism not underlie the predominant attitude of academic Leftists who expect a theoretician to tell them what to do?—they desperately want to commit themselves, but not knowing how to do so effectively, they await the answer from a theoretician. Such an attitude is, of course, in itself false, as if a theory will provide the magic formula, capable of resolving the practical deadlock (Žižek, First as Tragedy, then as Farce, 88).

There were a number of excellent papers at the Waiting for the Political Moment conference in Rotterdam last month, among which were keynotes from Benjamin Noys (which he’s put on line) and Jodi Dean (some of the key arguments of which are in this blog post). These two papers are interestingly read together, I think. Jodi argues that our concern about complexity and the difficulty of knowing enough functions as a kind of theoretical alibi for political inactivity:

There were a number of excellent papers at the Waiting for the Political Moment conference in Rotterdam last month, among which were keynotes from Benjamin Noys (which he’s put on line) and Jodi Dean (some of the key arguments of which are in this blog post). These two papers are interestingly read together, I think. Jodi argues that our concern about complexity and the difficulty of knowing enough functions as a kind of theoretical alibi for political inactivity:

The recourse to complexity is a move that says there is always more that needs to be known as well as unknown unknowns and unintended consequences of whatever it is that we end up doing. Such a move says, wait, stop, do you know what you are doing?

Benjamin, meanwhile, criticizes the tendency among political theorists to call for a (return to) concrete politics, a call often made by denigrating the abstraction of theory. Now, these two criticisms of contemporary political thought might seem to be in opposition to one another: Jodi calling for just the kind of concrete politics Benjamin considers inadequate, while Benjamin invokes, in the form of abstraction, the complexity Jodi is suspicious of. I don’t think that’s the case, though; in fact, the turn to the concrete and the retreat into complexity are two aspects of the same process.

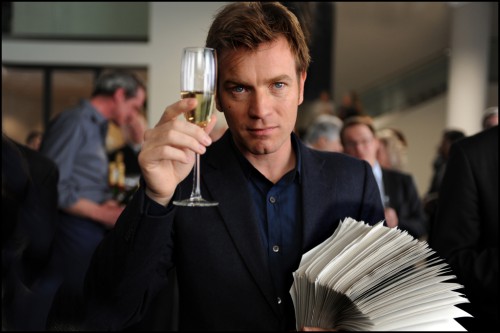

As luck would have it, on the flight over to Rotterdam, I saw a film which helps clarify the connection between these two perspectives. Roman Polanski’s The Ghost is quite entertaining and extremely stupid (as befits something based on a book by Robert Harris—I’m not sure it’s either as stupid or as entertaining as Archangel, though). The most interesting thing in the film, though, was the particular way in which the moment of revelation was delayed. At one point, the ghostwriter (Ewan McGregor) follows the GPS directions left in his predecessor’s car, ending up at the house of an academic who knew the prime minister (for whom McGregor and the previous ghostwriter were ghostwriting). The revelation, however, does not come through discussion with the academic, who, simultaneously avuncular and guarded, skillfully answers all the ghostwriter’s questions without revealing anything. The revelation occurs just a little bit later, when the ghostwriter types the academic’s name, along with “CIA,” into Google (there’s actually a further, even more hilarious, twist, which involves Ewan MacGregor solving an acrostic in the back room of a bookshop). A montage of link-clicking follows, in which the secrets of the film are laid bare.

This is the fantasy that links together the embrace of complexity and the rejection of abstraction. First of all, the call for concrete politics is always a philosophical or political-theoretical call, and, as a call, it is always at least one step removed from the concrete politics it desires (or purports to desire). Furthermore, what is supposed to allow us to take that step is one last theoretical effort, and it is this idea of the final resolution of theory through one last effort which underlies our relation to complexity: the idea is that we cannot act yet, but if we could finally master complexity, we would, at last, be able to act. As Jodi puts it in Publicity’s Secret:

A key technocultural fantasy is that “the truth is out there.” Such a fantasy informs desires to click, link, search and surf cyberia’s networks. We fantasize that we’ll find the truth, even when we know that we won’t, that any specific truth or answer is only a momentary fragment. Still, the fantasy keeps us looking. (8)

The fantasy, that is, is the one that Žižek criticizes, of a theory that would unravel complexity in such a way that it would immediately resolve itself into action, without us having to ever deal practically with this complexity (to choose, to act, to take a risk). This is also the kind of theory that Benjamin resists; the theory he proposes, a theory which attempts to understand abstraction rather than calling for the concrete, for all that it might assist us in deciding how to act, would not provide the alibi for action (or inaction) that, as Žižek says, is all to often what leftist academics look to theory to provide.