When can I go into the supermarket and buy what I need with my good looks?

JR asked on Twitter if I had anything to say about Selena Gomez’s “Who Says.” I didn’t think I did; it’s part of the recent trend of empowerment pop about which a lot has been written, although I like it more than “Firework” or “Fucking Perfect,” which are oddly, though actually not so oddly, joyless (“Firework” is tiresomely relentless in the way you would expect from Katy Perry, while “Fucking Perfect” continues Pink’s quest, since her first album, to make every record more boring than the last). The most interesting thing about “Who Says” is the video, in which Selena wanders through an LA in which the city furniture itself affirms her:

There’s something interesting about the importance this gives to commercial typography, which is something of a neglected art these days (of course we’re surrounded by commercial typography, but it’s no longer appreciated as an artform in the way I think it was in, say, the 50s).

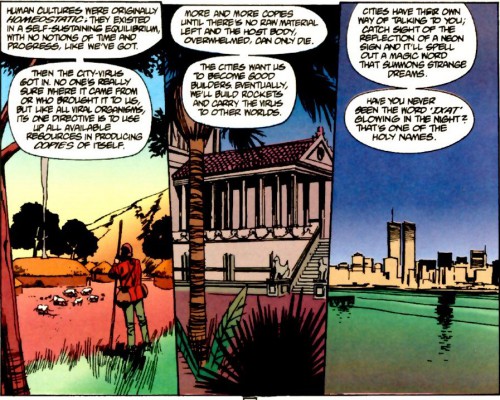

The video reminds me of Grant Morrison’s belief that corporate logos are secret sigils of magical power. Benjamin makes a similar point:

The video reminds me of Grant Morrison’s belief that corporate logos are secret sigils of magical power. Benjamin makes a similar point:

The writings of the Surrealists treat words like trade names, and their texts are, at bottom, a form of prospectus for enterprises not yet off the ground. Nesting today in trade names are figments such as those earlier thought to be hidden in the cache of “poetic” vocables. (The Arcades Project, G1a,2)

There’s something utopian about the “Who Says” video, about the idea of advertising that isn’t selling a product except for gentle reassurance. Benjamin writes well about the utopianism of advertising:

Many years ago, on the streetcar, I saw a poster that, if things had their due in this world, would have found its admirers, historians, exegetes, and copyists just as surely as any great poem or painting. And, in fact, it was both at the same time. As is sometimes the case with very deep, unexpected impressions, however, the shock was too violent: the impression, if I may say so, struck with such force that it broke through the bottom of my consciousness and for years lay irrecoverable somewhere in the darkness. I knew only that it had to do with “Bullrich Salt” and that the original warehouse for this seasoning was a small cellar on Flotwell Street, where for years I had circumvented the temptation to get out at this point and inquire about the poster. There I traveled on a colorless Sunday afternoon in that northern Moabit, a part of town that had already once appeared to me as though built by ghostly hands for just this time of day. That was when, four years ago, I had come to Lützow Street to pay customs duty, according to the weight of its enameled blocks of houses, on a china porcelain city which I had had sent from Rome. There were omens then along the way to signal the approach of a momentous afternoon. And, in fact, it ended with the story of the discovery of an arcade, a story that is too berlinisch to be told just now in this Parisian space of remembrance. Prior to this incident, however, I stood with my two beautiful companions in front of a miserable café, whose window display was enlivened by an arrangement of signboards. On one of these was the legend “Bullrich Salt.” It contained nothing else besides the words; but around these written characters there was suddenly and effortlessly configured that desert landscape of the poster. I had it once more. Here is what it looked like. In the foreground, a horse-drawn wagon was advancing across the desert. It was loaded with sacks bearing the words “Bullrich Salt.” One of these sacks had a hole, from which salt had already trickled a good distance on the ground. In the background of the desert landscape, two posts held a large sign with the words “Is the Best.” But what about the trace of salt down the desert trail? It formed letters, and these letters formed a word, the word “Bullrich Salt.” Was not the preestablished harmony of a Leibniz mere child’s play compared to this tightly orchestrated predestination in the desert? And didn’t that poster furnish an image for things that no one in this mortal life has yet experienced? An image of the everyday in Utopia? (The Arcades Project, G1a,4)

But this utopianism is double-edged, as it is itself an attractive quality that can be mobilized by advertisers; then the presentation of utopia becomes a demand that the viewer inhabit that utopia (presumably by buying the product). This is particularly true of pop songs which are, as it were, adverts for themselves, and explains (aside from the specific awfulnesses of Katy Perry and Pink) the joylessness of so many of these empowerment anthems: happiness becomes an obligation; I think this is what JR calls the “normative weirdness” of the genre. The songs brook no argument, they peremptorily tell the listener what they are (“you’re a firework,” “you’re fucking perfect”) or what they have to do (“don’t you ever feel…,” “don’t be a drag”). The indirection of “Who Says” kind of avoids this, by posing a question which encourages the listener to take a certain stance in response; there’s something positive, I think, about presenting empowerment as a performance that can be adopted rather than an intrinsic property (I thought of this because I misread JR’s tweet as being about “performative weirdness”). The idea of happiness as norm remains, though, which runs the risk of being all the more patronizing when its the pretty and successful Selena Gomez who is telling us to cheer up.

Which is a long winded way of saying that you should listen to “Love You Like a Love Song” instead of “Who Says.” LYLALS is by far the best thing Rock Mafia have ever done. The dubsteppy bass obviously draws on recent Dr Luke stuff in the manner you would expect from Disney’s in-house hacks, but it combines it with a fascinatingly melancholy in both the melody and the lyrics. There’s the ennui of the first line (“it’s been said and done / every beautiful thought’s been already sung”), and the extraordinary one-sidedness of the lyrics, which leave it completely unclear if the song is about requited, lost, or unrequited love.

The video also features Selena dressed as an androgynous robot butler, of which I approve. Also also, Allen Ginsberg reading “America,” from which the title of this post comes.

The video also features Selena dressed as an androgynous robot butler, of which I approve. Also also, Allen Ginsberg reading “America,” from which the title of this post comes.